I was talking to a female economist in my program recently. I told her that the rent on my apartment was going up by $50. "Did you try to negotiate that?" she asked. I did not. "Why?" she asked. I had no response. "You can always ask," she said. I had no response. I had no response because she was right.

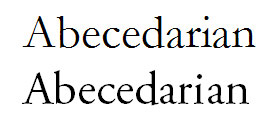

I read

Women Don't Ask yesterday. The general thesis of the book is that an important source of gender inequality in income and wealth is that women are much more averse to negotiation than men generally and don't ask for things when they should. I picked up the book after a friend talked to me about her having read it. This friend, like the female economist, is saddled with the supposedly sucker-spawning-second-x-chromosome, and yet is not still someone I really imagine being the type to leave all kinds of opportunities on the table because of an unwillingness to inquire on behalf of her interests.

I'm not disputing whether, in the aggregate, women are less likely to ask for things in "negotiation" opportunities than men are. Like virtually the whole of the literature on behavioral/psychological gender differences, I'm sure the female and male averages can even differ substantially while there remains overlap--meaning that there are women who aer very good about asking for things they want and men who are very bad at it.

I know for a fact this second category exists, because I am an exemplar of it.

In the nomenclature of Women Don't Ask, I negotiate like a girl. An extremely girly girl, in fact.

The book has all kinds of compelling anecdotes of women not asking in situations where they could ask. Many of these resonated with me all the way down to my allegedly androgen-soaked bones. "Me, exactly!" I wrote maybe some two dozen times in the margin, even though the protagonist of the anecdote was a woman.

Much of the book was also about why women don't ask, most of which relies on socialization arguments that focus heavily on upbringing and other earlier life experiences. As you can imagine, these parts didn't resonate with me quite so much, and I mostly skimmed them. All fine, perhaps, just not relevant for me, since I can't point around to "society's messages" about proper behavior and blame for them having trained me to be passive in ways often contrary to my well-being.

Instead, I get to wonder how I manage to be as bad as I am about asking for things despite the best efforts of countless agents of gender-order-reproduction to make me meeklessly manly.I would love to be able to blame this on how the only board game Sister D would play with me during one developmentally-vital period of my youth was

Barbie, Queen of the Prom, but I just don't think that is quite it. For parts having to do with asking-in-academia, I think there are ways that it's related to Imposter Complex Issues that are, in turn, related to my coming from a substantially lower economic and educational background than most of those now classified as peers/colleagues, but I think that line of explanation only goes so far, if it goes anywhere at all.

In any case, it's become increasingly clear to me for some time that not asking in cases where I could ask has cost me enormously professionally, personally-financially (as in the rent example above), and personally-personally. I'm not going to get into details here, obviously. It's more than a little painful to start doing the math just on the financial front alone. Less for the lost money per se than the sense of stupidity and suckerdom that goes along with it. And especially when you know that it's one thing to recognize that you have this needless costly aversion to being proactive about your situation and asking for things, but another to actually make improvements in dealing with it. Ugh.

One strategy of the book for prodding women to be more assertive is to argue that they are letting down the whole sisterhood when they don't. Meanwhile, I guess, at least I am doing my part to promote equality every time I'm a doormat.

World, your muddy heels are welcome upon my spine.